Gutenberg’s Printing Press: Susan Denham Wade (1454)

Susan Denham Wade

Few inventions have reshaped human society like the printing press. In this absorbing episode the author Susan Denham Wade takes us back to the year 1454, to a little workshop in the city of Mainz, to witness a magnificent moment in technological history.

*** [About our format] ***

In October 1454 the diplomat Enea Silvio Piccolomini (later to become Pope Pius II) arrived at the great Frankfurt fair. The annual event attracted people from right across Europe. Merchants carried wool from over the sea in England; there was Italian wine and Bohemian glass, and delights from the distant East like nutmeg, cloves and cinnamon.

The item that caught Piccolomini’s attention, though, was none of these. On display for the very first time was a curious collection of papers. At a glance they looked like the pages of an illustrated manuscript, the objects that had acted as the repositories of knowledge for hundreds of years. But this little run of papers had an entirely different feel. There was a striking regularity to the letters. They was so well-defined and accurate and were arranged in two perfectly neat columns across the paper.

Piccolomini was left astonished and excited. As he might instantly have guessed, what he saw was not a finished product. Instead it was one of a batch of quinternions – a collection of five folded sheets that made 20 finished pages – that were themselves just a small part of a grander project. In fact, what Piccolomini was seeing was something of a ‘product launch’ for Johannes Gutenberg’s magnificent Bible.

To read an exclusive, beautifully-illustrated extract of A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions, visit Unseen Histories. In this extract Susan Denham Wade takes us back to the invention of the new art of photography.

Within days of chancing upon Gutenberg’s quinternions, Piccolomini was writing back to his friends in Rome, telling them about his great discovery. It was clearly the work, he concluded, of a ‘miraculous man.’

*

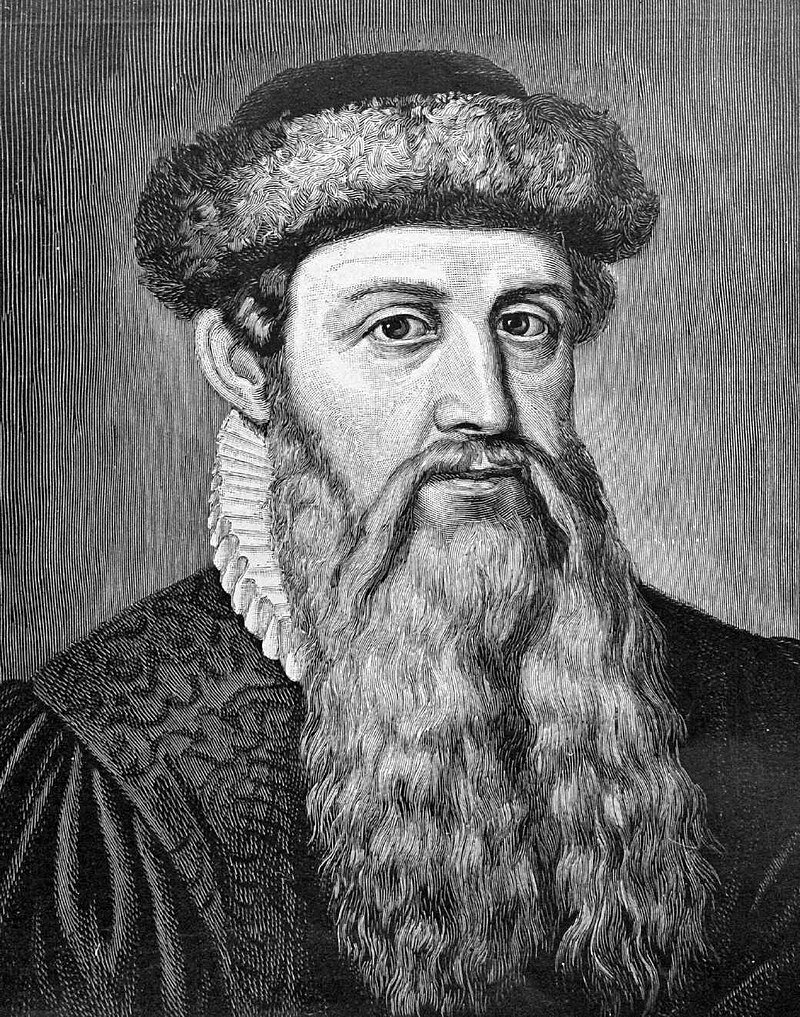

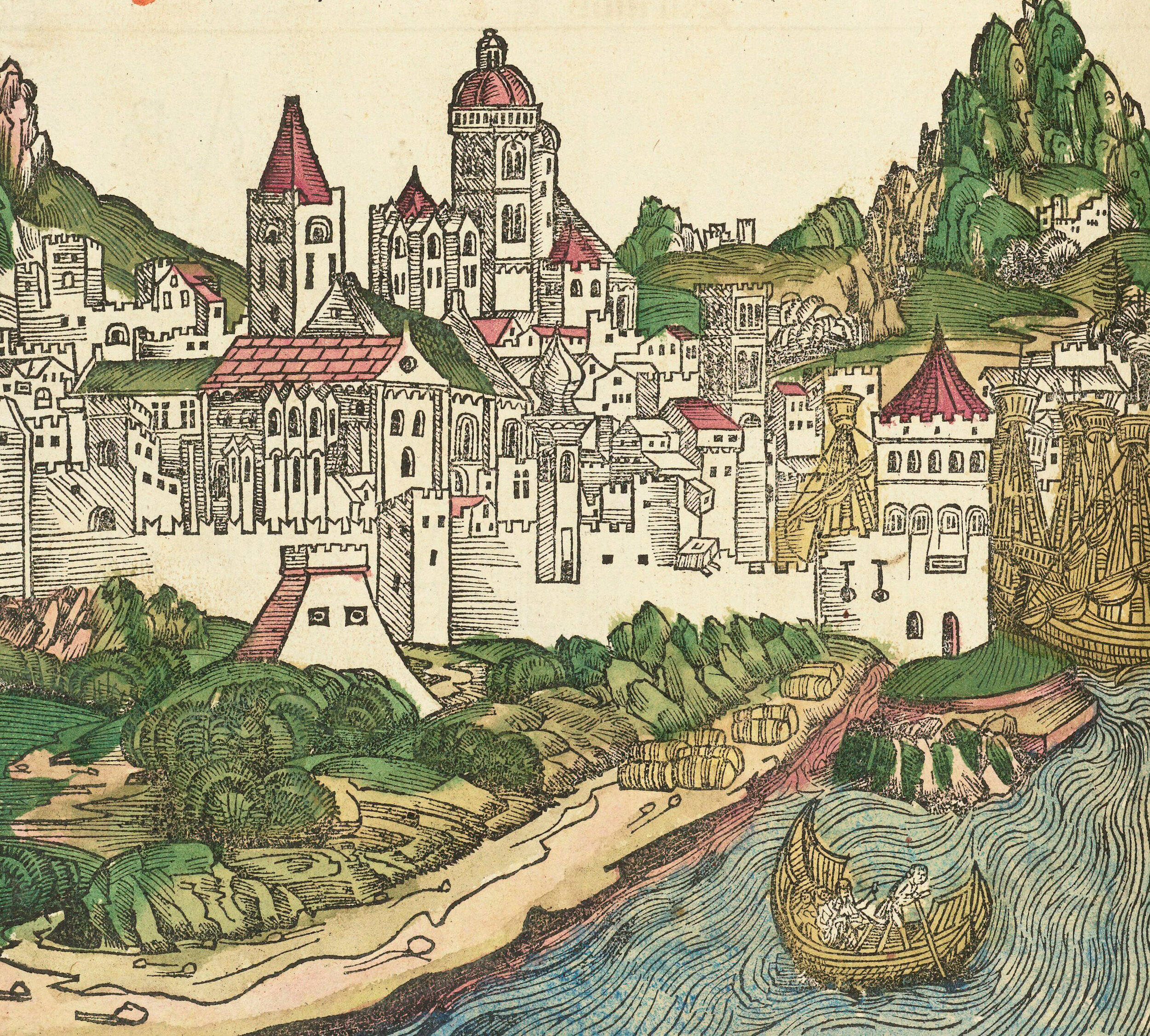

Johannes Genfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg was a native of the town of Mainz, which was situated on the banks of the River Rhine. Mainz was a lively centre of mercantile activity in the early fifteenth century, with goods arriving from river and with links to the heart of Renaissance activity in Italy to the south.

Gutenberg had lived in this world for around sixty years by the time that Piccolomini visited the neighbouring city of Frankfurt and encountered his work. Few details are known of his life during that time. The fragments of evidence tell us that Gutenberg was involved in a defamation case and that he worked for a time producing ‘Pilgrim’s Mirrors’. These were polished mirrors that were sold to pilgrims on the understanding that they had a special ability to soak up the holy power of relics that they encountered.

Before Gutenberg’s time, manuscripts had been rare and expensive objects. This depiction of university life in the fourteenth-century shows how people relied upon oral, instead of visual, communication. (Wiki Commons)

One thing is certain. Gutenberg was a master craftsman and by the 1450s he had alighted on the idea that would make his name. For years knowledge had existed in a frail state. It took teams of monks many months in scriptoriums to preserve the knowledge that did exist. The invention of woodblock printing during the previous century had promised a better, mechanised way of doing things, but this remained arduous. With a whole block required for each printed page, woodblock printing was only appropriate for the most modest of projects.

Gutenberg’s idea changed all of this. As Susan Denham Wade explains in this superbly analysed episode, he conceived of a printing process that depended on movable type. Whereas woodblock printing focused on a single page, Gutenberg’s system dealt in single letters that could be moved about to make any number of different words. Using his ingenuity, working with metals and moulds, he was able to fashion his elegant Gutenberg typeface. By 1454, this was the typeface that he had put to work on his grand Bible project.

Susan Denham Wade guides us through all this history in three perceptive scenes. She takes us back to a European world that was anxious after the Fall of Constantinople. Yet it was a world that was also full of a strange, dynamic, creative force that today we refer to as the Renaissance.

Brought together, the moments she isolates comprise some of the most important in human history. The printing press ultimately changed society from an oral-based one, to one that focussed on visual communication through the written word.

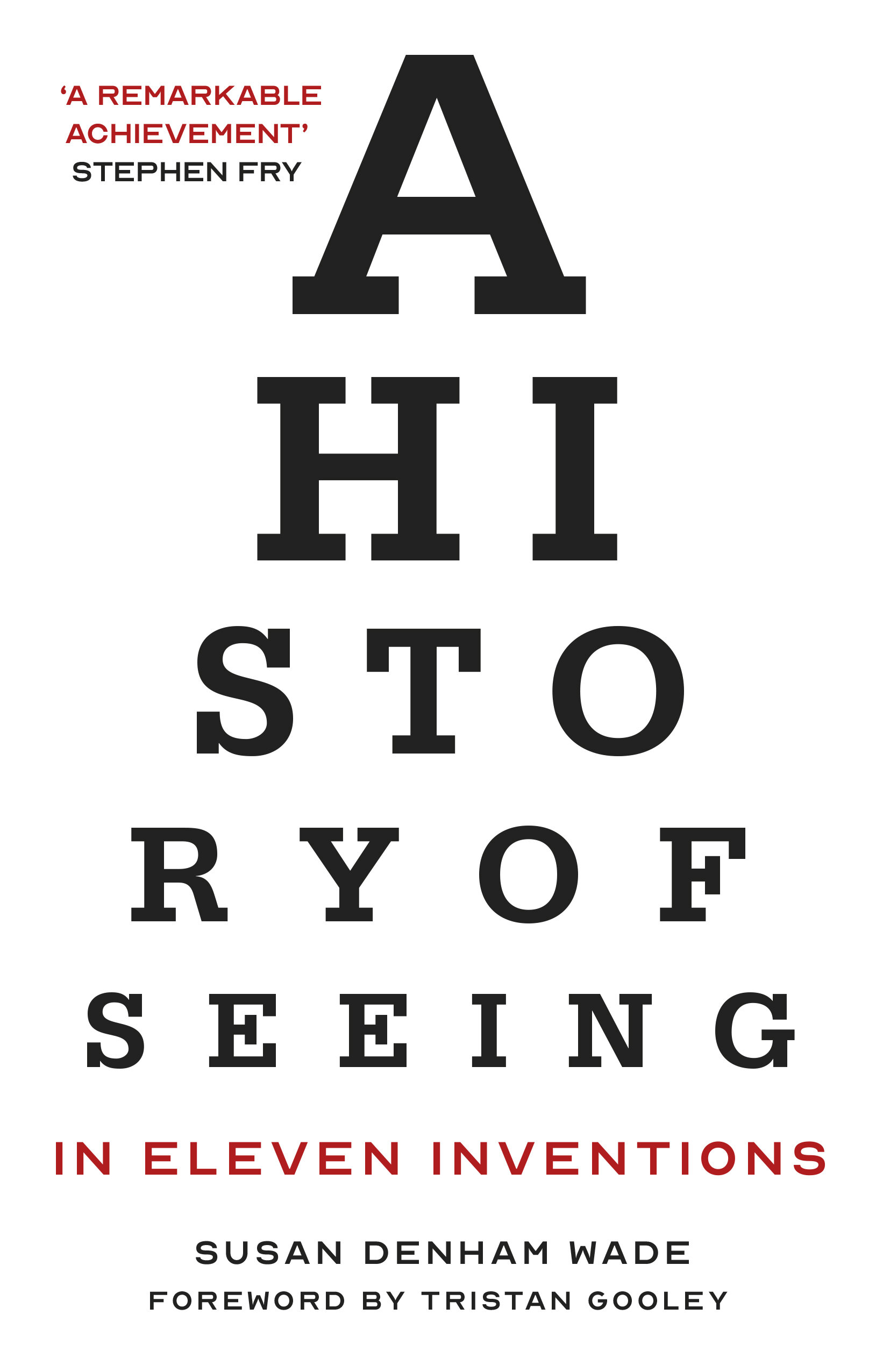

This shift is one of the eleven moments Susan Denham Wade defines in her book: A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions, a grand, sweeping survey of how perception and human culture and interacted over time. The book has been called ‘A remarkable achievement,’ by Stephen Fry.

***

Click here to order Susan Denham Wade’s book from John Sandoe’s who, we are delighted to say, are supplying books for the podcast.

*** Listen to the podcast ***

Show notes

Scene One: Mainz, Spring 1454. A middle-aged man delivers a parcel to an office in the Church of St Martin, wrapped in cloth. Inside are 200 printed indulgences. The man making the delivery is Johann Gutenberg.

Scene Two: Summer 1454. A workshop near a riverbank in Mainz, Germany. Gutenberg’s printing presses are working frantically to produce the monumental Bible project.

Scene Three: October 1454. Frankfurt’s famous trade fair. The Italian cardinal Piccolomini – future Pope Pius II, but at this point Bishop of Siena – catches a first glimpse of Gutenberg’s Bible. He is amazed at the beauty, accuracy and clarity.

Memento: A handful of original Gutenberg type.

People/Social

Presenter: Peter Moore

Guest: Susan Denham Wade

Production: Maria Nolan

Podcast partner: Unseen Histories

Follow us on Twitter: @tttpodcast_

Or on Facebook

See where 1454 fits on our Timeline

About Susan Denham Wade

Susan Denham Wade has an MA in Creative Writing (Non Fiction) from City University, where she was awarded the City Non Fiction Award, as well as degrees in Economics and Law and a Harvard MBA. She lives in West Sussex.

Check out the British Library’s digitised version of its copy of the Gutenberg Bible, as mentioned in this episode.

Mainz and Frankfurt

Image source: Library of Congress

More about the three scenes

Scene One:

Mainz, Spring 1454. A bustling Rhineland town in Germany. The town is dusty, or muddy, or both, noisy, smelly, busy. The mighty Rhine is the mercantile highway of the day. The town is walled. People and animals move around it constantly. Artisans, merchants, itinerant bards, musicians and players; scribes rush around with reams of paper under their arms, lots of clergy. Time is marked by bells. The town crier delivers news and messages, perhaps telling the townsfolk about the latest skirmishes with the Turks. It is just one year since Constantipole has been seized by the Ottomans.

A middle-aged man delivers a parcel to an office in the main church, wrapped in cloth. Inside are 200 printed indulgences. The man making the delivery is Johannes Gutenberg.

Scene Two:

Summer 1454. A workshop near a riverbank in Mainz, Germany. Gutenberg’s printing presses are working frantically on producing the monumental Bible project, overseen by the perfectionist inventor and entrepreneur. The operation is undertaken in secret.

Scene Three:

October 1454. Frankfurt’s famous trade fair. People from all over Europe come to trade goods – cloth, furs, precious metals, manuscripts. Italian Cardinal Piccolomini – future Pope Pius II, but at this point Bishop of Siena – is in town to try and persuade the German princes to raise troops to fight the Turks. He sees on sale quinternions - 5 sheets folded together to give 20 pages – of the Bible and is amazed at their beauty, accuracy and clarity. These are the first copies of the printed Bible, Gutenberg’s astonishing masterpiece.

A page from the Gutenberg Bible

Source: Wellcome Collection

Gutenberg Bible belonging to the New York Public Library.

Source: Wiki Commons

Listen on YouTube

Complementary episodes

Albert and the Whale: Philip Hoare (1520)

In 1520 the artist Albrecht Dürer was on the run from the Plague and on the look-out for distraction when he heard that a huge whale had been beached on the coast of Zeeland. So he set off to see the astonishing creature for himself.

[Live] Thomas Cromwell and Anne Boleyn: Prof. Diarmaid MacCulloch (1536)

In this wonderfully described episode, one of Britain’s greatest historians, Diarmaid MacCulloch, takes us back to the dramatic heart of Henry VIII’s Tudor court. The character in focus is one of the most fascinating of all: Thomas Cromwell.

Ruthlessness and Richard III: Thomas Penn (1483)

The death of the ‘charismatic but unreliable’ King Edward IV at Easter 1483 set in motion an infamous sequence of events. Within weeks Edward’s younger brother, Richard Duke of Gloucester, had seized power.