Rudyard Kipling, E.M. Forster and the Missing of the First World War: Robert Sackville-West (1915)

Robert Sackville-West (c) Jonathan Ring

The Armistice in 1918 might have brought an end to the violence. But for many families it did not mean the end of the story. In 1918 the whereabouts of more than half a million British soldiers alone remained unknown. These were often very young people, drawn from all walks of life, right across Britain. They were people who had simply vanished into the battlefields.

In this episode Robert Sackville-West takes us back to those desperate times a century ago. He shows us three examples of how people attempted to come to terms with the loss of a loved-one. This was a loss made all the more painful as there was very often no body and no explanation.

*** [About our format] ***

On 2 October 1915 a distressing telegram arrived at Bateman’s, the Sussex home of the Nobel-Prize winning writer Rudyard Kipling. It carried a brief message. The Kiplings’ son, John, had disappeared during fighting at a place called Chalk Pit Wood, five days earlier. John was a second lieutenant in the Irish guards. He had been leading his platoon into action in a British offensive, later to be known as the Battle of Loos.

A little more than a month before, John Kipling had been a seventeen-year-old boy at home at Bateman’s. Carrie, his mother, had jotted a nimble picture of him in down in her diary, looking ‘very straight and smart and young, as he turns on the stairs to say; “Send my love to Daddo.”’ Soon afterwards he had celebrated his eighteenth birthday and crossed the Channel to France. Over the days ahead a few, threadbare details emerged of his movements on the day he went missing. One man had seen him limping, obviously wounded. Another thought he had seen him fall. “Your son behaved with great gallantry and coolness,’ explained a letter from John’s commanding offer, Captain John Bird, ‘and handled his men splendidly.’

John Kipling - 1897 - 1915. (Wiki Commons)

Over the days, months and years that followed the initial telegram, Rudyard Kipling would devote himself to discovering the truth of what had happened to his son. As no body was recovered, he always knews there was a chance that John had been captured by the Germans, or that he had been taken to a hospital with amnesia. Four years would pass before Kipling would admit that John was almost-certainly dead.

The Kiplings’ anguish was deep and prolonged, but as today’s guest Robert Sackville-West, explains, it was by no means rare. Throughout the war families right across the country would receive similar telegrams to that which arrived at Bateman’s. Often the information they contained was inchoate and inconclusive. With so much death (or suspected death) to report, officials frequently fell back on euphemism or stock phrases to describe a soldier’s final moments.

Families were left to respond in their own distinctive ways. As Sackville-West explains in this moving episode, some, like the Kiplings, rejected the idea of death. To give up on missing relatives seemed, to many, to be the ultimate betrayal. Others reinterpreted the nature of their loss. While accepting the fact that a person’s physical presence had gone, they retained a conviction that that missing person could be contacted in the spiritual world.

Most of all, Sackville-West contents, people took solace in the act of ‘searching’. Professional searchers - people like the writer E.M. Forster - scoured the hospitals and the barracks for clues about the missing. In the age of Sherlock Holmes these searchers were like civilian detectives, working on the most perplexing and painful of all cases: the hunt for the missing of the First World War.

***

Click here to order Robert Sackville-West’s book from John Sandoe’s who, we are delighted to say, are supplying books for the podcast.

*** Listen to the podcast ***

Show notes

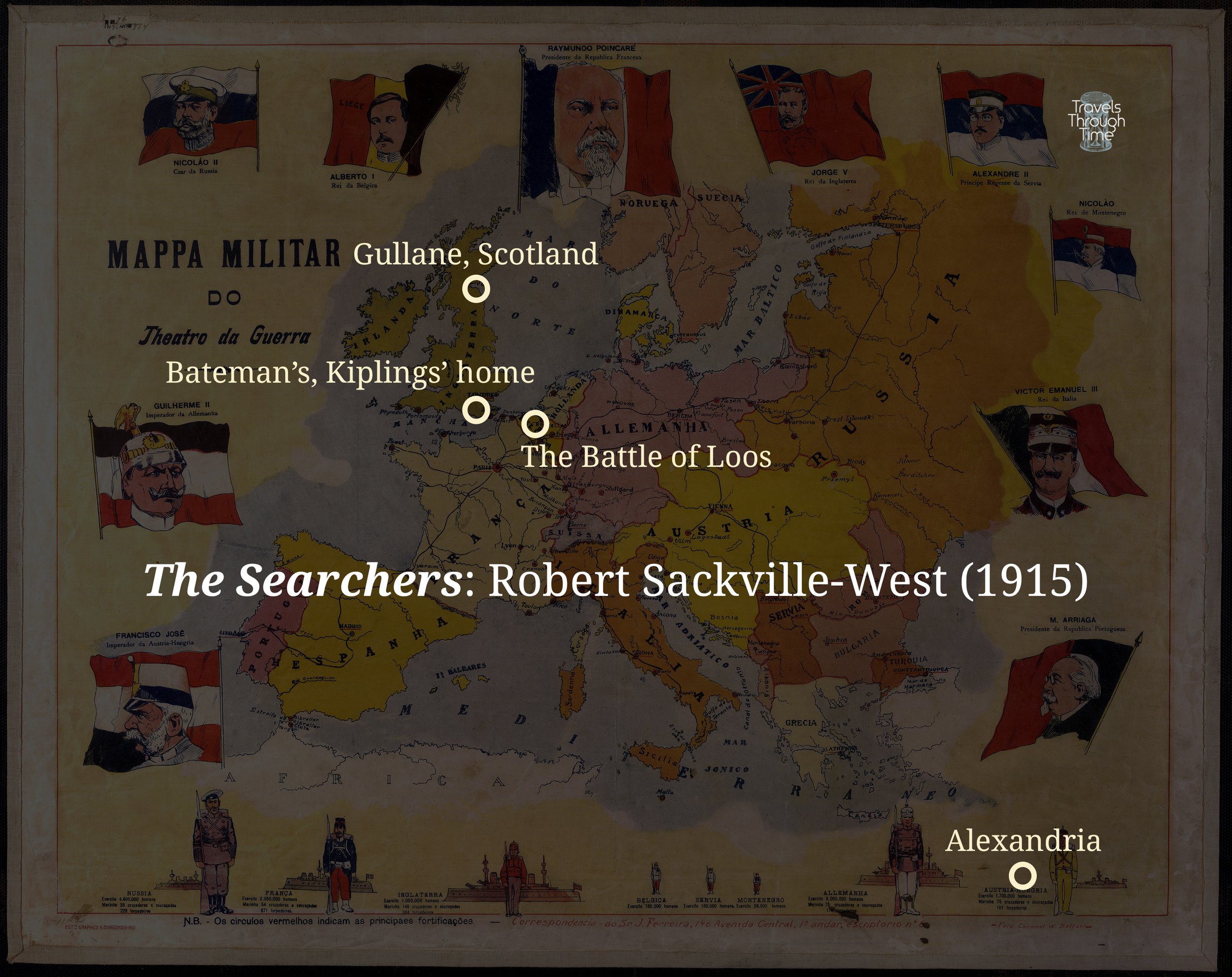

Scene One: 2 October 1915, a distressing telegram arrives at Bateman’s, the home of Rudyard Kipling.

Scene Two: 15 September 1915, Sir Oliver Lodge is playing golf at Gullane, on the east coast of Scotland.

Scene Three: November 1915, The novelist E.M. Forster arrives in Egypt as a Red Cross ‘searcher’.

Memento: An identity tag.

People/Social

Presenter: Peter Moore

Guest: Robert Sackville-West

Production: Maria Nolan

Podcast partner: Unseen Histories

Follow us on Twitter: @tttpodcast_

Or on Facebook

See where 1915 fits on our Timeline

About Robert Sackville-West

After studying History at Oxford University, Robert Sackville-West worked in publishing. He now chairs Knole Estates, the property and investment company which – in parallel with the National Trust – runs the Sackville family’s interests at Knole, the house in Kent where his family have lived for the past 400 years.

Robert is the author of the critically acclaimed Inheritance: The Story of Knole and the Sackvilles (2010) and The Disinherited (2014).

Map of the Scenes

Background map: Library of Congress

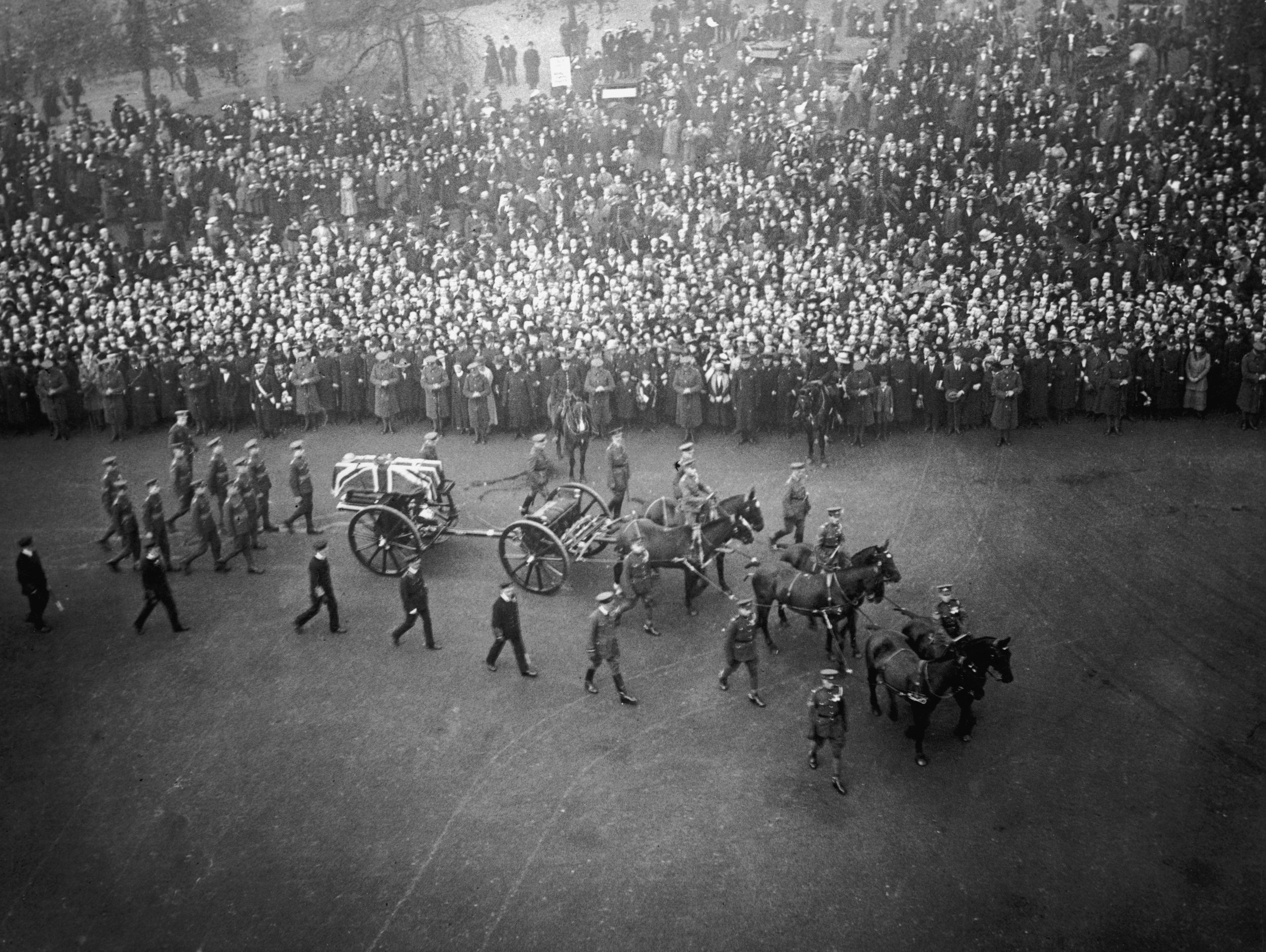

British soldiers parade past the Cenotaph in the Peace Day celebrations of July 1919. © Getty Images

The coffin of the Unknown Warrior is pulled in procession through the streets of London 1920 © Getty Images

Scene One: 2 October 1915, a distressing telegram arrives at Bateman’s, the home of Rudyard Kipling.

John Kipling, an officer in the Irish Guards, is last seen at the Battle of Loos. Five days later, the Nobel Prize-winning writer Rudyard Kipling and his wife, Carrie, received a telegram reporting him missing. They spent the next four years hoping to establish that he was still alive, but when the weight of evidence convinced them that he must be dead, they spent the rest to their lives trying, unsuccessfully, to locate his grave on the Western Front. It was an irony that the man who had chose the phrase ’Their Name Liveth for Evermore' for the cemeteries where so many hundreds of thousands were buried had no shrine, stone or grave at which to lay his own grief.

Scene Two: 15 September 1915, Sir Oliver Lodge is playing golf at Gullane, on the east coast of Scotland.

On the morning of 15 September 1915, Sir Oliver Lodge was playing golf at Gullane, on the east coast of Scotland. Although he had been greatly looking forward to the round, the eminent physicist, and founding Principal of Birmingham University, ‘was in an exceptional state of depression’, and could barely hit the ball. At the time, he did not ascribe any particular significance to his mood that day; in retrospect, however, he interpreted it as one of several premonitions. Two days later, he received the standard-issue telegram from the War Office that his son Raymond had been killed. But whereas Rudyard was to search obsessively for his son on the battlefields of the Somme, Sir Oliver Lodge turned to mediums and the spirit world to contact his son, Raymond, in the afterlife.

Scene Three: November 1915: The novelist E.M. Forster arrives in Egypt as a Red Cross ‘searcher’.

The novelist E.M. Forster arrived in Egypt as a Red Cross ‘searcher’, working for a now-forgotten organisation, The Wounded and Missing Enquiry Department. He expected to be there for three months, but in fact spent the next three years touring the hospitals of Alexandria, asking soldiers wounded in the disastrous Dardanelles campaign, for news of comrades who had been reported missing. Every evening, he filed a report that was forwarded to the London Office of the Red Cross, and eventually sent to the families of the missing men. The city was the backdrop to his first proper love-affair, and to the happiness and fulfilment he found with Mohammed el Adl, a young Egyptian tram conductor. Forster found that he was rather good at the job, ending up as Head Searcher for Egypt. Day after day, he sat beside the beds of the wounded, teasing from them the jagged shards of their most traumatic memories and transferring them to a notebook. Sometimes he simply played chess and Patience with the soldiers, or ran errands for them, lent them books, wrote letters that they dictated. The whole experience was therapeutic for all.

Listen on YouTube

Explore other years from World War One

The Bolsheviks and the Lockhart Plot: Jonathan Schneer (1918)

How close did we come to a world without the USSR? A world with no Stalin, no KGB, or even Putin today? In this episode of Travels Through Time we head back to 1918 and the scene of an audacious plot to find out.

Square Haunting: Francesca Wade (1917)

In this episode of Travels Through Time the biographer Francesca Wade takes us to the fringes of London’s Bloomsbury, to explore a fascinating generation of poets, writers and publishers who passed through Mecklenburg Square.

Total War: Simon Heffer (1916)

The mood across Britain at the end of 1915 was one of disbelief. A war that many had predicted would be over in months was only intensifying. There was stalemate on the Western Front. Newspaper columns were filled with examples of German “frightfulness”, such as the execution of Edith Cavell, and there was growing doubts in Westminster about Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s ability to lead the country.

D.H. Lawrence, Burning Man: Frances Wilson (1915)

We delve into a dark and turbulent year in the life of one of Britain’s most controversial literary geniuses – D.H. Lawrence. Our expert guide is Frances Wilson, whose latest book, Burning Man: The Ascent of D. H. Lawrence focuses on the middle period of the writer’s life between 1915 and 1925.

Radical Resistance: Dr Diane Atkinson (1914)

1914 is a year most commonly associated with the beginning of a world-changing war. But as hostilities broke out on Continental Europe, in the towns and cities of Britain a different kind of conflict was already well-underway. In this podcast Dr Diane Atkinson takes us from the squares of England’s […]