The Mercenary River: Nick Higham (1837)

This week we head to nineteenth century London, when the city's infrastructure was groaning under the strain of its exponential growth and the question of how to get a clean, reliable water supply was of upmost importance.

*** [About our format] ***

We take running water in big cities like London for granted now, but for most of our history we’ve not had access to it. When did we first start pumping water up from the Thames? How did people wash themselves when they didn’t have bathrooms? Why has water been privatized or nationalized at different stages in its history?

These are all questions that my guest today, Nick Higham, answers in his new book The Mercenary River. Stretching from the medieval period to the modern, Nick’s book charts the technological and scientific breakthroughs that made London’s water what it is today. He dives into the murky politics of this most essential of resources, and offers vivid glimpses into how water was used in daily routines.

In this episode we meet some of the characters who were helping turbo charge the capital’s water supply in 1837, and those who were polluting it. From the mighty steam engine that helped pump water across the city, to the women who did the laundry until their hands bled, this episode shows how, in Nick’s words, “water supply touches our lives and the history of society in so many different ways .”

The Mercenary River is published by Headline and is available to pre-order here.

*** Listen to the Podcast ***

Show Notes

Scene One: 1837. A few yards back from the banks of the river at Kew Bridge near Brentford, where the Grand Junction Waterworks is building a new pumping station well upriver from its original Thames intake in Chelsea, which was at the mouth of a major sewer. It has been embarrassed into making the move by the outcry occasioned in 1827 by The Dolphin, a pamphlet which for the first time highlighted the appalling, disgusting quality of most of London's water. The water's filthiness is partly thanks to the growing popularity of flushing water closets, whose effluent now ends up in London's rivers rather than property owner's cesspits.

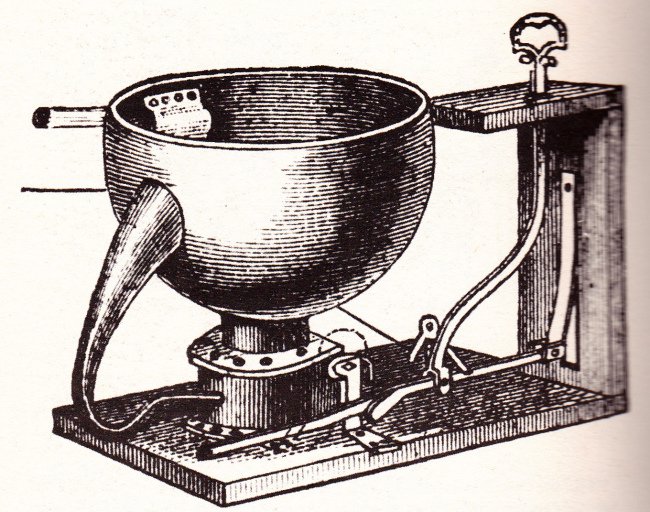

Scene Two: 1837. Cornwall, where the talented young engineer of the East London Waterworks, Thomas Wicksteed, has gone to buy a second-hand steam-driven pumping engine for the East London's intake on the River Lea at Old Ford. The machine Wicksteed buys is of a new-fangled design developed for Cornish mines which is up to six times more powerful and efficient than previous generations of engines: Wicksteed has had difficulty persuading his directors that the performance figures are genuine, but in due course the Cornish engines he introduces to London will become the water industry's workhorses. As it happens, Wicksteed and the East London are ripped off, paying far more than the machine is worth -- which is not untypical of the early 19th century business world.

Scene Three: 1837. Buckingham Palace, where the newly-crowned Queen Victoria is taking up residence and is (presumably) unamused to discover there is no bathroom. Many medical experts still think baths (especially hot baths) are dangerous to health. But personal hygiene is not completely neglected. The young Queen perhaps uses a portable hip-bath or a moon bath, standing "like a pink lighthouse" to soap herself down before the bedroom fire. And like every other affluent person her linen underclothes will be washed frequently: they absorb her sweat and smell, but doing the laundry is arduous work (almost exclusively done by women) which often leaves the laundresses' hands bleeding and, in homes smaller than Buckingham Palace, is incredibly disruptive.

Momento: One of the minute books of the water companies.

People/Social

Presenter: Artemis Irvine

Guest: Nick Higham

Production: Maria Nolan

Podcast partner: Ace Cultural Tours

Follow us on Twitter: @tttpodcast_

Or on Facebook

See where 1837 fits on our Timeline

About Nick Higham

Nick Higham hails from London and is a journalist who has spent 30 years at the BBC: fifteen as their arts and media correspondent and also hosting 'Meet the Author' on the BBC News Channel. His interest in London's water began with the New River, which originally ran to New River Head on the borders of Islington and Clerkenwell, within sight of the building housing the London Metropolitan Archives where much of his book was researched.

Featured Images

Listen on YouTube

Complementary Episodes

Journey into Deep London: Tom Chivers (62 AD)

In this episode we visit London in 62 AD, barely twenty years after it was first established by the Romans, to traverse its lost landscape and hidden waterways.

London’s Blackest Streets: Sarah Wise (1889)

For this insightful and evocative episode, Peter Moore heads to the historian Sarah Wise’s flat in central London, to talk about left wing politics, life and labour in the imperial capital in the year 1889.