Wolfson History Prize Special: Professor David Abulafia (1415)

In this episode of Travels Through Time we are taken on an invigorating tour of the ports, coasts and oceans of the world with Professor David Abulafia – winner of the 2020 Wolfson History Prize for his book, The Boundless Sea.

The year 1415 is commonly remembered in Great Britain as the year of King Henry V’s sensational triumph at the Battle of Agincourt. But while the Welsh arrows were raining down in northern France, out across the globe historical processes of an even greater magnitude were taking place.

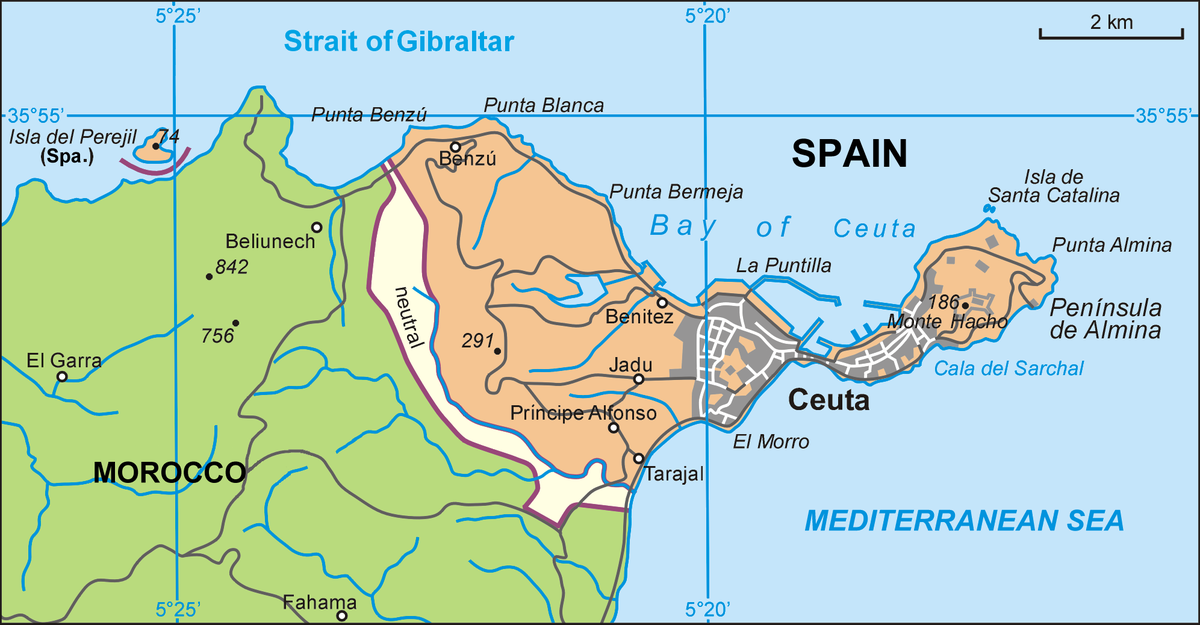

On the northern coast of Africa, across the Strait of Gibraltar, lay the wealthy and strategically important trading port of Ceuta. For centuries this had been a bustling place of commerce, where the caravans bringing goods up from central and western Africa had met the vessels of Mediterranean merchants.

In 1415 Ceuta was seized in a surprise attack by the relatively impoverished kingdom of Portugal. This decision by the Portuguese court to make Ceuta the target of their huge naval crusade took all of Europe and the Islamic world by surprise. No one thought Portugal possessed the money or vessels for such a campaign against a strongly-fortified city that other powers had failed to conquer. The surprise was all the greater because the new Portuguese dynastry kept its plans a closely guarded secret.

Check out Wolfson History Prize winner David Abulafia discussing the world's oceans in 1415 on the latest @tttpodcast_ episode, featuring a surprise Portuguese invasion, Greenland's dwindling trade, and the mysterious fleet of Admiral Zhenghttps://t.co/npLhsvPKsE @wolfsonfdn

— Wolfson History Prize (@WolfsonHistory) August 11, 2020

Among the belligerents on the streets of Ceuta that day was the son of the king, Henry the Navigator. The capture of Ceuta has ever since been interpreted as the opening of the Portuguese Golden Age, and an event that led directly to the voyages of Vasco da Gama and Ferdinand Magellan. This, as Abulafia explains, might not quite be the whole story.

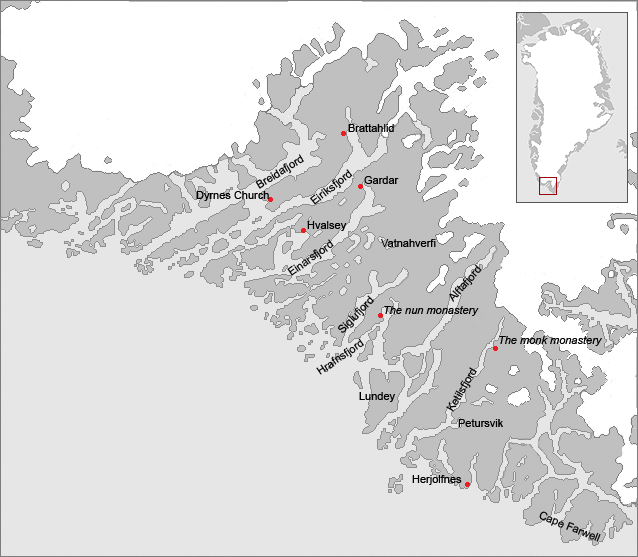

As the Portuguese established themselves as a rising power in Europe, far to the north in Greenland the long-established Norse communities were vanishing from their settlements. For centuries these communities had been fully enmeshed in the global network of trade, sending skins, ivory, falcons and other consumables to Europe. But in the early fifteenth century the annual visits of ships from Norway ceased, leaving the settlements isolated. Historians have long speculated what was behind this. Was it changes in the pattern of trade? Was it a cooling climate?

“The Boundless Sea tackles a world encompassing subject: humanity’s constantly changing relationship with the seas that cover most of our planet and on which our very lives depend. This is a book of deep scholarship, brilliantly written and we extend our warmest congratulations to David Abulafia”

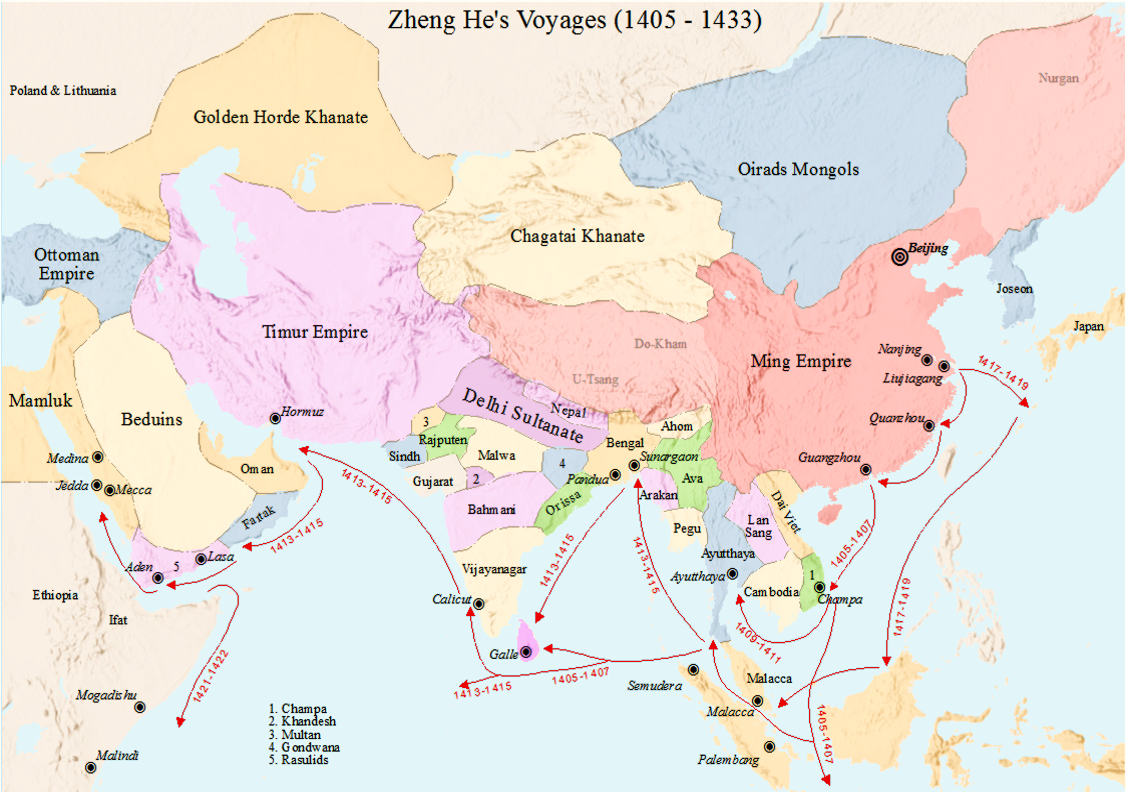

And then, at the far side of the world, we head to Nanjing China to take a look at the mysterious fleet of Admiral Zheng. Between the years 1405-34 Zheng led seven expeditions out into the Indian Ocean to locations as distant as Zanzibar and the Strait of Hormuz. These voyages comprised scores of ships and their purpose has long been debated among historians. Here Abulafia hints at an answer.

David Abulafia is Emeritus Professor of Mediterranean History at the University of Cambridge.

Click here to order David Abulafia’s book from John Sandoe’s who, we are delighted to say, are supplying books for the podcast.

Listen to the podcast

Show notes

Scene One: August 1415, The Portuguese attack on Ceuta, North Africa

Scene Two: 1415, The Eastern Settlement Greenland

Scene Three: 1415 Nanjing, east coast of central China & the Indian Ocean

Memento: A piece of Chinese porcelain from Nanjing

People/Social

Presenter: Peter Moore

Guest: Professor David Abulafia

Producers: Maria Nolan

Titles: Jon O

Follow us on Twitter: @tttpodcast_

Podcast Partner: ColorGraph

*** PRIZE *** - Want to be in with a chance of winning a signed hardback copy of Dan Jones’s Crusaders? - Just subscribe to our newsletter over there —>

(Competition closed - Congratulations to Jo Bailey, whose name came out of the digital hat)

“Walrus hide was valued in northern Europe because it could be twisted into rough rope. A Greenland falcon made a perfect gift for the falcon-crazy Emperor Frederick II in thirteenth century southern Italy; twelve Greenland falcons are said to have constituted the ransom paid for the crusading son of the Duke of Burgandy when he was captured by the Turks in 1396. Greenland did, therefore, play a role in the international trade of the Middle Ages, and was by no means a disconnected territory inhabited by Norse exiles. ”

Image: Greenland. Indigenous fishing; three different whales; whale fisher in their attire. Coloured etching. Wellcome Collection

Listen on YouTube

More about the scenes by David Abulafia

Scene One: 21 Aug 1415 – 22 Aug 1415, Ceuta, North Africa

The Portuguese conquest of this city on the northern tip of Morocco, often seen as the start of the process by which they created a great maritime empire (though I wouldn’t accept that interpretation). But it was the first time an impoverished kingdom on the furthest edge of western Europe had launched an ambitious and expensive campaign some way beyond its own borders. In one way it was a precursor to the great Portuguese voyages of exploration: Ceuta had been (maybe was no more) a major terminal point for the caravans carrying gold across the Shara desert, and there was a gold shortage within Europe, quite apart from the fact that any ruler had his (in one or two cases her) eye on how to increase the amount of gold in the treasury. A second way this was significant is that we are introduced to the ambitious, foolhardy, often fantasizing Portuguese prince Henry ‘The Navigator’, who, apart from Ceuta, didn’t navigate anywhere himself, but began the process of colonisation of the Atlantic islands (foundation of sugar industry in Madeira, etc.), and started the exploration of the coast of West Africa – and when they couldn’t at first find gold, they took away slaves instead, marking the beginning of the large-scale trade in black African slaves towards Europe.

Scene Two: The Eastern Settlement, Greenland

Around 1415 there were still Scandinavians living in Greenland, as there had been for over 400 years, but the history of their settlement was coming to an end. For centuries they had traded in walrus ivory brought down from further north by enterprising Norse sailors, along with bearskins and live polar bears and falcons. These products were sent towards Iceland or directly to Bergen, the Norwegian capital, where German merchants gathered in the confined area known as the Bryggen that still survives (though they were also very keen on dried codfish). Back in Greenland, the Norse made regular visits to northern Canad in search of wood. They encountered increasing numbers of Inuit (Eskimo) who were gradually moving south towards the two settlements they possessed in Greenland. But it is possible climatic conditions were deteriorating and that the ships to and from Norway were sailing less and less often. Priests sent from Norway also dd not arrive. Isolation was probably killing off these communities and by the end of the century they had vanished – but where to? Quite possibly to North America, which they would not have recognised as a vast new continent.

Scene Three: Nanjing, China, 1405-34

Admiral Zheng He’s voyages into the Indian Ocean – seven mysterious expeditions were launched as the Ming emperor proclaimed his power across the known world, or at least that is one explanation, but there are many others (the search for a rival who might usurp his throne; the search for the Buddha’s tooth in Sri Lanka, etc.). These expeditions traversed massive distances, all the way to East Africa and even up the Red Sea to the outport of Mecca, which was visited by Chinese Muslims on board the fleet. Exotic products of the Indian Ocean such as giraffes were ferried back to China. Rebels in Java were suppressed. In the descriptions we have, the fleets sound enormous: vast ships, lots of them, built in the shipyards of Nanjing, and thousands of troops on board; more recent research suggests the figures are an exaggeration. What is particularly odd is that the voyages were a flash in the pan, mainly encouraged by the so-called Yong’-e Emperor, and then shut down after less than thirty years.

Maps (scroll to view)

Featured images

Complementary episodes

From Pole to Pole: Sir Michael Palin (1841-8)

In this first episode of Travels Through Time Michael guides us back to the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign. The 1840s were crucial years in the history of British exploration with speculative voyages towards the North and South Pole. One ship, […]

Mansa Musa’s Pilgrimage to Mecca: Luke Pepera (1325)

In this episode of Travels Through Time, the writer and broadcaster Luke Pepera introduces us to Mansa Musa, a dazzling figure in African history. Mansa Musa was the Emperor of Mali in the fourteenth century and we follow him as he embarks on his spectacular pilgrimage to Mecca in 1325.

Click here to order The Boundless Sea by David Abulafia from our friends at John Sandoe’s Books.

A decade after his superb history of the Mediterranean, Prof Abulafia has extended his canvas to three immense oceans – the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian. (John Sandoe’s)

About the Wolfson History Prize

First awarded by the Wolfson Foundation in 1972, the Wolfson History Prize remains a beacon of the best historical writing being produced in the UK, reflecting qualities of both readability for a general audience and excellence in writing and research.

The most valuable non-fiction writing prize in the UK, the Wolfson History Prize is awarded annually, with the winner receiving £40,000, and the shortlisted authors receiving £4,000 each. Over £1.25 million has been awarded to more than 100 historians in the prize’s 48-year history. Previous winners include Mary Beard, Simon Schama, Eric Hobsbawm, Amanda Vickery, Antony Beevor, Christopher Bayly, and Antonia Fraser.

To be eligible for consideration, authors must be resident in the UK in the year of the book’s publication (the preceding year of the award), must not be a previous winner of the Prize and must have written a book which is carefully researched, well-written and accessible to the non-specialist reader.

To learn more about the Wolfson History Prize please visit https://www.wolfsonhistoryprize.org.uk