D-Day: Dr Peter Caddick-Adams (1944)

Operation Overlord was one of the critical moments of the Second World War. It began on 6 June 1944 when the Allied forces landed around 150,000 troops on the beaches of Normandy in France.

Today, 6 June 1944 is commonly remembered as D-Day. Within a year of that date Europe was liberated, the NAZI regime was totally defeated and its figurehead Adolf Hitler was dead.

*** [About our format] ***

In this episode of Travels Through Time, the lecturer and military historian Dr Peter Caddick-Adams takes us back to May and June 1944.

We watch the final exercises for D-Day going forward across the south coast of England and then we travel across the Channel with the Allied forces to the operational beaches: Omaha, Utah, Sword, Juno and Gold. The events that happened at this time and across these places would change the course of twentieth century history.

***

Click here to order Peter Caddick Adams’s book from John Sandoe’s who, we are delighted to say, are supplying books for the podcast.

Listen to the podcast here

Show notes

Scene One: 2/3 May 1944, Operation Fabius, south coast of England

Scene Two: 15 May 1944, The Thunderclap Conference. St Paul’s School, London. Final briefing for Operation Overlord.

Scene Three: 6 June 1944, Sword Beach, Normandy, France.

Memento: General Wilhelm Falley’s hat

People/Social:

Guest: Peter Caddick-Adams

Presenter: Peter Moore (@petermoore)

Producer: Maria Nolan

Titles: Deft Ear

Explore more World War 2 Podcasts

Listen on YouTube

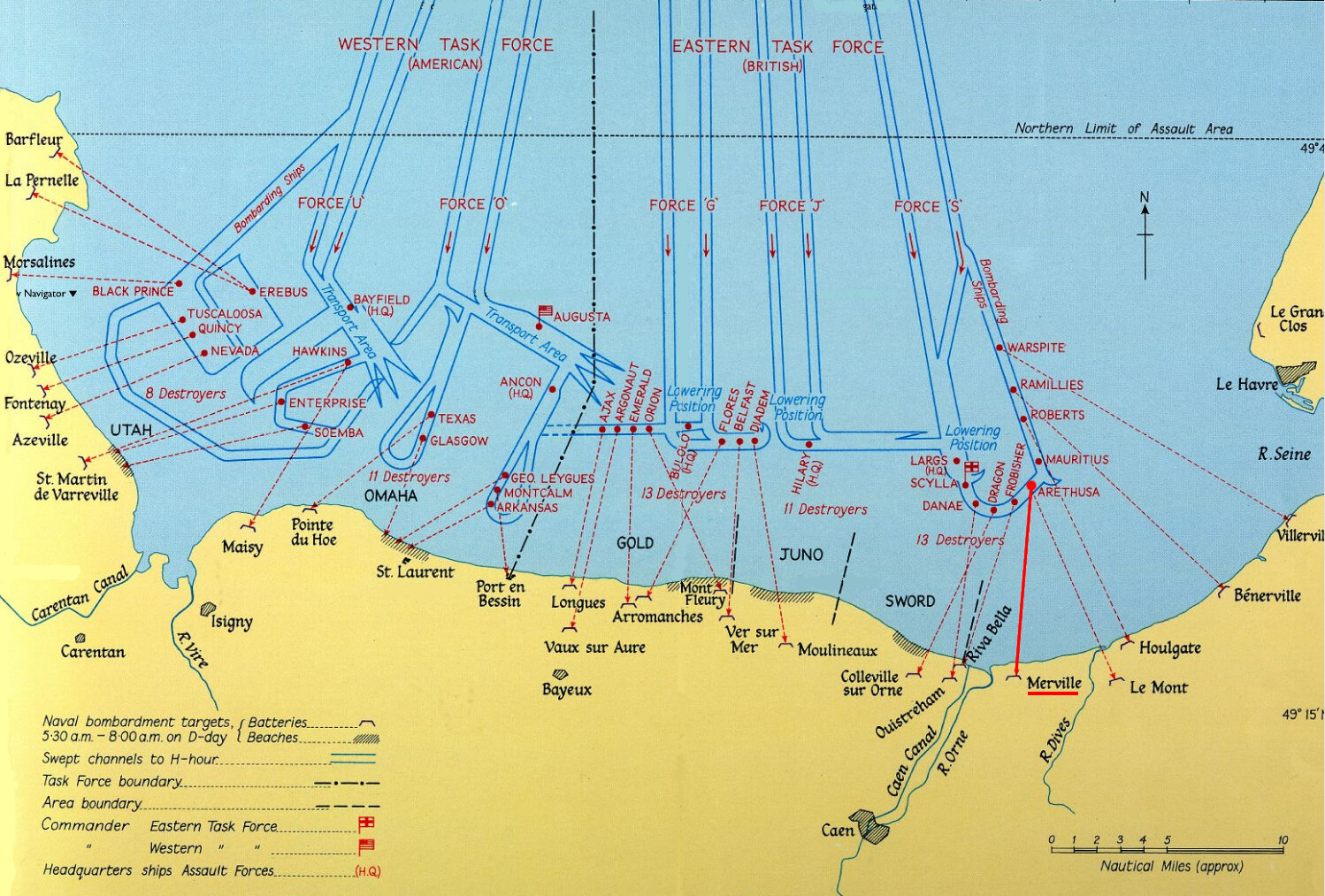

Map

Map source: Library of Congress

Naval Bombardment Targets, D-Day

Image credit: WikiCommons

Complementary episodes

Walking with Destiny: Andrew Roberts (1940)

In seventy two hours in the middle of May 1940, Britain’s political leadership was transformed. Out went the undistinguished, dithering government led by Neville Chamberlain, known for its failed policy of appeasement. It was replaced by a new regime of ‘growling defiance’, […]

Wolfson Prize Special: Prof. Mary Fulbrook

The Holocaust is the bleakest, blackest, most disturbing moment in our human story. It involved the systematic murder of millions of Jews, minority and vulnerable groups by the Nazis during their reign of terror in Europe in the 1940s.

American troops marching through the streets of an unknown British port town on their way to the docks to commence Operation Overlord (Wikkicommons)

Click here to order Sand & Steel by Peter Caddick-Adams from our friends at John Sandoe’s Books.

Transcription

[Intro music]

Hello, and welcome to Travels Through Time. In each episode of this podcast, we invite a special guest to take us on a tailored tour of the past. Travels Through Time is brought to you in partnership with History Today, Britain's best-loved, serious history magazine. You can read articles relating to this podcast and more about our guests at historytoday.com/travels. There is also a special subscription offer for Travels Through Time listeners - three issues for just £1 each.

Peter Moore: Hello, I'm Peter Moore. Let's begin this episode by travelling back to the start of June 1944. Here is General Dwight D. Eisenhower addressing the Allied troops on the eve of D-Day.

[Voice of Ryan Bernsten]: 'Soldiers, sailors and airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force. You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade towards which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms in other fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of the Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe...'

Peter Moore: Welcome to a special D-Day anniversary episode of Travels Through Time. It's 75 years since the 6th June 1944, when 150,000 Allied troops were landed on the beaches of Normandy in France in a single day. The beginning of Operation Overlord, or D-Day as it's commonly known, was also the beginning of the end of the Nazi war machine in Europe. It's also commonly remembered as the most famous military operation of the Second World War. I'm going to be exploring this history with an expert guest, as ever, in three pivotal scenes. Today's guest is the lecturer and military historian Dr Peter Caddick-Adams. Peter has taught at Cranfield University and at the UK Defence Academy for much of the past two decades. Through his lecturing and writing, he's established a reputation as being one of the foremost military historians of his generation. His published works include a study of the five-month Monte Casino campaign in 1944 and a joint biography of Bernard Montgomery and Erwin Rommel. Peter's latest book, Sand and Steel: A New History of D-Day, documents the history of the plans and execution of Operation Overlord in forensic detail. James Holland, the writer, has called Sand and Steel a 'superb and timely book that will change our overview of D-Day forever.' I met Peter at his publishers in London the other day to talk about one of the most famous dates in all 20th-century history.

Welcome to Travels Through Time, Peter.

Peter Caddick-Adams: Thank you. I'm very happy to be here.

Peter Moore: Good. My first question to you is what draws you to the history of the Second World War? Has it always been an interest for you?

Peter Caddick-Adams: My mother took me to see the movie Battle of Britain when it came out when I was ten years old and that hooked me forever. She was very clever because she'd been ten years old when the real battle had been fought and so she wanted to introduce me to the sort of terror and context of her upbringing. Little did she know that that took me into making plastic model kits and then reading and studying both world wars. Of course, at that time, every adult had done something interesting in the Second World War and so that hooked me. It was talking to the veterans wherever they'd fought.

Peter Moore: The Second World War, this period of 20th-century history, is very well written about and very well researched. How much new is there to say about it?

Peter Caddick-Adams: That's a very good question and you might think that it's all done and dusted but even from the Napoleonic era, 200 years ago, we are discovering papers, letters and diaries in trunks and in attics. There is always something new to discover. I think one of the interesting things is that we now have the advent of forensic archaeology. Archaeology never lies and with modern techniques, we can piece together the past of either world war and much, much further back in a way that was impossible even ten years ago.

Peter Moore: I know at the start of your book, you write about your childhood visits to the Normandy beaches and you talk about some of the defences that are still there. You were managing to gather together bits of ammunition that were still lying around on the floor. Is that right?

Peter Caddick-Adams: That's absolutely right. In 1975, my parents let me travel over to Normandy with some friends. We were on the invasion beaches and we met a chap in a kilt with a pair of bagpipes and this turned out to be Piper Bill Millin, who was then the age I am now, so in his 50s. He was playing his bagpipes up and down the beach that he had landed on in 1944 and that completely mesmerised me. He took us along the beach and pointed out the German bunkers which were still there. I remember, the following year, whilst our family sat and sunbathed on the beach, I dug the bunkers and there, in the sand, were bullets and shell cases from the Second World War. You can imagine the effect on a 14 or 15-year-old.

Peter Moore: Yeah, it's a strange confluence between the idea of leisure and relaxing on the beach but then having all this history so close by and the two of them coming together. I suppose we might often go on holiday to read a history book but then, in your childhood, you had history just behind you waiting to be explored.

Peter Caddick-Adams: I think there's something deep within you, if you're a historian by vocation, that you want to reach out and touch the past and whether you're going to the American Civil War and walking down a trench or at Waterloo and you reach out and touch the walls of Hougoumont farmhouse. On Normandy, there's so much more. There is all that concrete architecture from the Atlantic wall. There are the sand dunes and the barbed wire, in many cases, just as with the trenches of the First World War. I think that's what brings history alive. You can see it and you can take yourself back mentally to be a figure in the dramas of the past.

Peter Moore: That's a perfect way of setting us up for our travels because this is exactly what we're going to be doing. We're going to go back to this time, 1944, and examine an enormous story through three little scenes, which might be a way of bringing the history back to life, I hope, for this podcast at least. The first scene that you've chosen is Operation Fabius.

Peter Caddick-Adams: Fabius, after a Roman emperor.

Peter Moore: This is on 3rd and 4th May 1944. Do you want to tell us what this operation was, what was happening and where we are?

Peter Caddick-Adams: The Allies have assembled millions of troops. There are two and a half million Canadians, Brits and Americans in Southern England waiting to leap and spring across the Channel. They don't know when or exactly where they're going to go, just their commanders, but they need to be exercised en masse in the final technique of an assault landing against France. Each division, all the supporting ships, the artillery, the engineers, the medics and everyone involved is going to be inserted into a last mass exercise to practise them in everything they've learned over the preceding year. What we have to remember is the Allied soldiers who are going to arrive in France have an average age of 21 and most of them have been rehearsing for at least the previous year. The Germans are mostly in their late 20s, 30s and sometimes 40s, so they're much older, less fit and they just don't have that operational training, experience or understanding of firing live weapons, in many cases. Some of them are recruits of only four weeks' training. We go back to the Allied soldiers and they need a huge exercise which will just take them through their paces and confirm everything they've been doing. This is Exercise Fabius. It's launched simultaneously for four of the five assault beaches. The troops that land on Sword, Juno, Gold and Omaha are going to be exercised all the way along the South Coast from Dorset, Hampshire and right through to east and west Sussex. It happens simultaneously. We can say it's the largest amphibious exercise ever launched in history. It's over 100,000 men, all the landing craft and aircraft, you name it. In fact, just like D-Day, the weather is so appalling, it's postponed for 24 hours and that's just fortuitous. That's what Exercise Fabius is. There is a build-up period and everyone is concentrated. They get on their ships and they then assault, invade inland and mop up. The amphibious phase of that is two days, 48 hours, on 3rd and 4th May. There are a few days before and a few days after. The moment that ends, the troops go into lockdown to prepare for D-Day. If you like, it's phase one of D-Day.

Peter Moore: The thing that's just so striking when you're talking about this is the sheer number of people because we've had lots of scenes in this podcast but probably none which encompasses such a panoramic landscape as the South Coast, pretty much half of it at least. It was such a large amount of people. I think you talk about the numbers in detail at the beginning of the book and this is an amount of people of about three million, which swells the British population from 47 to 50 million in total. Is that right?

Peter Caddick-Adams: Yeah, the number of Americans, Canadians, free French and Poles arriving during the Second World War is well in excess of three million. If you take a lot of the Brits away who are serving overseas, it means that out of every ten adult males of fighting age, between 18 and 40, in the UK at that time (population then 40 million), four are going to be from overseas and principally American. The effect on the United Kingdom is just mind-blowing and it's something we forget. Three million American visitors passed through during World War Two, mostly in 1943 and 1944, and the effect on the home population is enormous; never mind the Canadians as well and all the other varieties of soldiers from Europe, who have escaped and are going to return. I tripped over so many memories of families who'd adopted an American, or a Pole, or a Canadian, that stayed in touch with them but sometimes they didn't come back. A lot survived the war and stayed in touch with their families for decades afterwards and it just showed you how close that bond was during the war.

Peter Moore: So there was a level of integration within British society with the GIs and the other soldiers but what about on this particular day? Were they all on very different beaches? The Canadians here and the British here doing their practice?

Peter Caddick-Adams: That's exactly right. The Americans are concentrated in the Weymouth, Dorset area. The Brits assaulting Gold Beach are in the Isle of Wight, Hampshire area and the Canadians attacking Juno Beach are very near there. Further along in Worthing and Littlehampton, you've got the British assault forces who are going to go over to Sword Beach. They're pretty much opposite to the beaches that they will have been attacking. That's why Fabius is so fascinating because it's such a huge undertaking and yet it's completely faded from public consciousness. There's a very good reason for that and that is the fifth beach, Utah. They had their exercise the month before and this was Exercise Tiger and that had gone wrong. The Germans had bumped into it in the middle of the night and had torpedoed some of the ships. They didn't know their good fortune in terms of disrupting this and the American had lost nearly 1,000 casualties. When we look back, all the drama about the rehearsals and the build-up to D-Day, everyone's attention is focused on Exercise Tiger. These other exercises have nothing like those casualties, yet the scale is much, much larger and they're just as important, if not more so, but we've completely allowed them to fade from history. That's what I'm doing. I'm the collector of stories. I'm handing on these tales and reviving aspects of D-Day that have been lost.

Peter Moore: Of course, it's an operation which is inherently very dangerous, not just because you've got so many people and there are probably new technologies and equipment being tried out for the first time and just to manage that number of people is difficult. However, we know Winston Churchill has been talking in the House of Commons last year saying, 'What we and our American allies judge to be the right time, this front will be thrown open and the mass invasion of the Continent will be begun in the West.' There's obviously a general understanding that an invasion is imminent. Is it like an open secret or is there still a measure of subterfuge which is going on?

Peter Caddick-Adams: It's a very open secret. Even the Germans know that something is about to happen. Their defences have been built up but they're being bombed every night. All the Atlantic Wall concrete bunkers are being attacked and all the rail lines, the roads, the bridges and even canals leading into France are being hit by the RAF heavy and medium bombers, along with the Americans who have largely been switched from a lot of their targets they're attacking in Germany. The Germans understand that France is going to be attacked but they just don't know where or when. It's exactly the same for the Allied soldiers. They're taking bets on what day or what part of France. In late April, Eisenhower says to Churchill, 'We've got to be so careful with secrecy. What I want is a lockdown of the South Coast.' Churchill grumbles that this is contrary to democracy but Eisenhower insists and the other British chiefs of staff support him. If you live on the South Coast or, indeed, within ten miles of it, you're not allowed in or out of that zone and that would probably affect millions of people. If you live there, you can't leave it. If you're from outside, you can't enter it. All mail is stopped from the Royal Mail to be distributed around the country for two weeks and diplomatic bags are suspended. A lot of people don't even know that this is happening but it's just to stop any leak that would give the Germans a clue.

Peter Moore: So a sense of bewilderment, along with probably a mounting excitement that there's going to be a progression in the war.

Peter Caddick-Adams: Oh, undoubtedly. Everybody realises this. If you read The New Yorker magazine, their correspondent in England writes that 'England, right now, resembles a giant warehouse full of equipment labelled 'Europe'.' She's allowed to write that because it's so obvious and it's in general terms but, of course, it's a morale raiser. Everyone in America has huge expectations and everyone in England knows what's going on. In some cases, the German morale is quite high because they have their best general, Rommel, waiting but the whole world is bubbling with excitement. I can't really put it better than that. There's this huge electricity in the air that something is about to happen.

Peter Moore: Just a supplementary question really because we know a lot about the Enigma machine and the interception of German messages through the top lines of their military which has been happening at Bletchley Park for a long but was there something similar happening the other way around or not really?

Peter Caddick-Adams: No, exactly and again, this has largely been wiped from history. We focus on Bletchley partly because the secrets of Bletchley were denied to us for three decades. The secret was only let out in 1974 and before then, because we were going to use the same techniques against the Russians, it was all kept extremely under wraps. The Germans have all sorts of codebreaking organisations and so they're not exploiting one top-secret code because we use several and we're more multinational but they do break some of the infantry exercise codes. They break the small ships' codes used by the Royal Navy. They're reading the codes used by British Railways moving troops and supplies around and so they know there is a movement down to the South Coast of landing craft, Royal Naval vessels, trains, men and equipment. They're aware of movements of aircraft across the Atlantic and the build-up of glider troops and parachute troops in Southern England. All the clues are there but we are clever enough and tight enough, in terms of security, not to give them any pointers as to exactly where or when but they start to make educated guesses.

Peter Moore: Obviously, the invasion is going to be in the Pas-de-Calais. That's where the British are heading because it's the place with the harbours. That's the place where there is the shortest crossing of the Channel. This is probably the message they're trying to get out. Is it a bluff?

Peter Caddick-Adams: The easiest way to put it is if you stand on the cliffs at Dover, you can see France or vice versa and that's what we have to remember. That's why it's never going to work for the Allies because the Germans could see what was happening and if we'd launched an attack there, they would know straight away, so that's the ruse. However, we're in danger of overplaying that as historians. The Germans had built up all their defences around there and they're now beginning to think elsewhere.

Peter Moore: Let's leave it there because I think this is the perfect point to go on to your second scene which is on 15th May, a fortnight after the great exercises on the South Coast. This is the Thunderclap conference. Can you explain what this is and where this took place?

Peter Caddick-Adams: There are actually two Thunderclap conferences. One is held at the end of April but the 15th May one is the crucially important one and this is where all the top leaders assemble. By that, I meant the entire upper echelons of government from the United Kingdom, from the dominions like South Africa and Canada and everyone resident in London. You've then got all the military commanders who take place and are commanding Operation Overlord from Eisenhower down and they all assemble in one room, which is Montgomery's headquarters. Funnily enough, that's at his old school in St Paul's, West London.

Peter Moore: That's near Brook Green, is it not?

Peter Caddick-Adams: Exactly so. He'd been a boy there 50 years earlier or more than that. Not surprisingly, he then commandeers the headmaster's study as his own office. This is his event and this is where he sells Operation Overlord to everybody else. We've got to remember that, in context, the last amphibious operation was at Anzio in January 1944 which doesn't go very well. We've got Salerno and Sicily where the Germans mounted very severe counter-attacks and they nearly failed. We've had things like Dieppe. Churchill's own experience was of writing the papers and strategy for Gallipoli. So amongst the whole senior echelons of the Allied commanders, there is great nervousness that D-Day could go wrong and, of course, it's a one-shot weapon. If for any reason it fails, then Churchill's credibility is on the line and certainly for our A team of people like Eisenhower and Montgomery, could their reputations survive? The Allies couldn't do Normandy again if we got it wrong because of all the investment in deception and so it has to work. I think the troops at the tactical level, the lower commanders and even the generals, divisional commanders, are confident but at the upper level, there must have been huge nervousness. This is where Montgomery presides. Thunderclap is his conference and if there are any doubts that people have before they walk into that conference, when they come out, it's Montgomery who is really sold the idea and they all walk out bubbling full of confident and that's Montgomery's doing.

Peter Moore: You've written about Montgomery before, haven't you? You know him well. What kind of a character was he? I noticed something that amused me when I was reading your book. You said he had a spaniel called Rommel and he had a foxhound that answered to the name of Hitler. Is this right?

Peter Caddick-Adams: Oh, absolutely. I think that very senior commanders are so focused on the professionalism of their job that it makes them quite antisocial. They become almost monk-like figures. They're above, beyond and away from the normal banter. He didn't really follow art, culture or anything else. It makes you so remote. What you want is company and actually, animal company is safe because they can't take and give secrets and they receive but they don't necessarily give. It's a sort of one-way trade.

Peter Moore: So a reserved character, happy in the company of his animals and obviously with a great reputation as a general behind him already.

Peter Caddick-Adams: Rommel is doing exactly the same. He's got a pair of miniature Dachshunds. You see the same traits with commanders, which is absolutely fascinating.

Peter Moore: It is, isn't it? I suspect most people will know the bones of what Operation Overlord was but what were they told that day? There's going to be an assault on the beaches of Normandy. Were they given the exact locations, the codenames for the beaches and which divisions were going to be sent against which beach?

Peter Caddick-Adams: Everything was laid out in full. Everybody there was security cleared. There were just over 140 gilt-edged invitations sent out. It was a bit like a summons to something at Buckingham Palace, which is very apposite because His Majesty the King was there, sitting in the front row with Winston Churchill. It was a freezing cold day and so everyone was wearing greatcoats and they're sitting on ordinary school benches, except Churchill and the king who have armchairs. That's austerity wartime Britain for you. Montgomery is at the front and he leads and then all his commanders follow briefing their parts. What they've done is they've laid out a huge map of the actual invasion coastline. It's in an auditorium with tiered seating and everybody is told exactly what's going to happen and when. Very importantly, Montgomery talks through the whole campaign and how he sees it unfolding over the 90 days; not just D-Day but ever after. The American General Omar Bradley, in his memoirs, talks about Montgomery 'tramping around Lilliputian France' because all the details are there [laughter] representing the actual terrain.

Peter Moore: I liked some of the little details that stick in your mind, namely the beaches, of course. Most people will remember them as Omaha, Utah, Sword, Juno and Gold. Was it not Juno as Jelly to begin with and Churchill didn't like that and so he had that name amended?

Peter Caddick-Adams: Yeah, the three British/Canadian beaches are Gold, Sword and Jelly and they're all kinds of fish. Churchill, in 1943, had cottoned on to the fact that the Allies were coming up with some very weird codenames. He didn't want the difficulty of being able to say to a widow or the next of kin, 'Your husband died on a beach called Jelly,' in this case and so he had the codename changed.

Peter Moore: We've got Omaha and Utah beach and you talk about that as well in the book and how there's a bit of mystery over the naming of those because it's never actually been shown where those names came from. There are suggestions that maybe they were named after American GIs. Is that right?

Peter Caddick-Adams: It's curious. Being a historian, you sit on received wisdom all the time. No one had sat down and really teased out where Omaha and Utah had come from. If you did, the story was usually that it was connected with the two American VII and V corps commanders, whose home states were allegedly Omaha and Utah but Collins and Gerow don't come from either of those states. That was wrong and so I dug a bit deeper and the story I uncovered was that when Bradley had his headquarters renovated in West London, in Bryanston Square, there were two GI carpenters who were reorganising his office where he could hang his maps. One came from Omaha and the other came from Utah. There was a lot of banter between these two and General Bradley and they would often queue up for coffee together and doughnuts. It's the GI way. Commanders, officers and men rub shoulders far more than in the British Army. At one stage, Eisenhower joined in this little banter and the question was asked, 'What are we going to name these beaches?' Bradley had said, 'Omaha and Utah because that's where you two come from.' This is contained in someone's little notebook contemporary with the period. It's very difficult to find other proof of that but it's a nice little pebble to throw in. The point about Thunderclap was that there were really two options. Do we go to the Pas-de-Calais, as we've just discussed, or do we go to Normandy? This was selling the conclusion that the Allies had come to that the commanders had reached that - 'We have to rule out Calais because it's too obvious and it's too close. You could never cram all the men and machinery into the Pas-de-Calais area because the Germans would be able to see it so easily. Normandy adds an element of mystery and surprise and therefore, we're choosing this for these reasons.' It's not just revealing what we're going to do. It's selling it as well to everyone who is there.

I mentioned that the king was in the front row and, of course, we know a bit about King George VI from The King's Speech. He's not a natural speaker but at the end, he stood up and he addressed everyone and said, 'This is a wonderful undertaking and I wish us well. I can see how much hard work we've put into this and it will be successful.' His private secretary said afterwards, 'I never expected His Majesty to speak.' It was a spur of the moment decision and there was none of the difficulty that he had felt making public speeches and announcements before. It just shows you how much he's grown and matured as an individual and grown into his role.

Peter Moore: Brilliant. There's nowhere that we can go now, apart from the obvious date which is 6th June. This is going to be your third scene. This is a date that you remark right at the beginning of your book that 'there was no day in history quite like 6th June 1944'. I know you want to take us to a particular beach with a particular character and so can you pick up the story of what's happening?

Peter Caddick-Adams: It is such a gamechanger of a day. We look back and it's perhaps the defining day of the Second World War, certainly in Europe. Even on the day, people would have realised how important it was. It's not one of those things where you suddenly look back and the analysts of history say, 'That was the pivot. That was the tilting point.' Everybody arriving off Normandy, taking part in it, sitting in a headquarters monitoring what's going, even the Germans would have suddenly realised just how important that day was even before they locked horns with their opponents.

Peter Moore: Just geographically, which one?

Peter Caddick-Adams: That's the British beach on the extreme eastern edge of the invasion front. This was where William the Conqueror came from in 1066.

Peter Moore: So it's already got a historical significance to the British.

Peter Caddick-Adams: Yeah, and William the Conqueror's deputy was a guy called Roger de Montgomery, whose descendent is Bernard Montgomery who is going back. There is a sense of everything coming full circle.

Peter Moore: It's a strange echo, isn't it?

Peter Caddick-Adams: Even the Americans and Canadians (Brits in origin, many of them) would have realised that this was bizarrely history coming full circle.

Peter Moore: What is Sword Beach like as a beach geographically and the terrain of it? Is it a great big sweeping one? Is it contained within a bay?

Peter Caddick-Adams: Off to the east, not too far away, you've got the big port of Le Havre and so the worry there was German artillery coming in from the east and so we had quite a lot of Royal Naval support just off the beach in the form of battleships. The idea was to pound the French coast and suppress the defensive fire coming from the battleships. If I sketch it out, what we've got is a sandy beach, inland where the beach huts would have been and a casino, very famously, at Ouistreham. The Germans have demolished most of the seafront buildings and they've built quite a lot of concrete gun positions. Forward of those are obstacles on the foreshore designed to prevent tanks from moving inland or to wreck landing craft as they approach the beaches with plenty of barbed wire and mines. You would have seen that tracking further west where you would have had the Canadians landing on Juno about five miles away. Beyond them, Juno Beach, British 50th Division, a big gap either side of the artificial harbour at Arromanches and then about 12 miles beyond that, you've got the Americans landing at Omaha, which is the biggest beach at five miles long. There's then another large gap and around the corner, where the terrain then turns north with the Cherbourg peninsula, you've got the beach of Utah. Those are the five beaches. We've had paratroopers who've gone in ahead of us on either flank. If you imagine the beaches as an inverted left hand and the thumb is Utah beach and the four fingers are the other invasion beaches. Your little finger is Sword Beach and the British are landing there at 7.25 on the morning of Tuesday 6th June.

Peter Moore: Wow! Are we with a particular person?

Peter Caddick-Adams: Let's go back to the person I met when I was 14 in 1975 on Sword Beach. This is Piper Bill Millin, who is a wonderful guy. Clearly, at the age of 21, this was the most defining moment of his life. He had grown up in the Scottish Highlands and had become the personal piper to the dashing Commando Brigadier Lord Lovat, who was then in charge of the 1st Special Service Brigade which comprised four British Commando battalions. In the headquarters' element, Lovat, who lived in a castle, liked to have his piper with him everywhere; to pipe him into dinner even and had Millin play him ashore. He'd asked Millin, much earlier in the year, 'I want you and I want you to play bagpipes and play me ashore.' Millin had said, 'Sir, bagpipes are now banned by the War Office because they alert the enemy and they're considered rather old-fashioned.' Lovat was of the old school and he said, 'Ah, but that's the English War Office. You know it doesn't apply to us.' So he had his way and there was Bill Millin and, as he told me, he marched down the ramps playing his pipes. The first thing that happened, he said, 'I was wearing my kilt and, as is traditional, nothing underneath. So as I hit the extremely cold English Channel, the temperature played havoc with my anatomy and it was a struggle to carry on playing the pipes. My kilt rose up and floated on the ocean for a while and it spread around me like a tartan jellyfish,' which is a great visual image.

Peter Moore: All of this is modifying my image of D-Day because all the sounds you expect to hear on those beaches, like the whistling of gunfire, the shouts of people coming ashore and the splashing and the bagpipes aren't probably what you'd expect to hear but they were going on Sword Beach.

Peter Caddick-Adams: It's all about morale and that's partly why the British Army and every army have taken instruments into battle. They're a weapon of war and it raises morale. You suddenly realise you're not alone because even if you can't see him or her, there's someone there playing an instrument on your side, a tune you remember, and all of a sudden, you're not alone. In days gone by, of course, those tunes were instructions; hence, bugle calls, drum rolls and all the rest of it. That's why music is so important all the way through the military. Here is a very good example of it on a D-Day beach. You run ashore, you bury yourself in a sand dune so that the bullets aren't going to get you and you hear the piper. Now Bill Millin can't run and hide. He has to walk up and down the sand playing his pipes while the brigadier works out what's going on and issues his instructions. That removes the ability of other men to run and hide because if Bill Millin is standing around with his pipes, you can't be a coward and hide and so it coaxes men out of the sand dunes. If they see young Millin playing his pipes, then... you can see how it raises morale and induces people to do their duty.

Peter Moore: What an extraordinary spin on a familiar story that is though because if you think about it logically, musical instruments have been used as weapons right throughout history. We were talking about the Battle of Hattin, which is in the Crusades, a few weeks ago and the same thing was happening there. It's just a constant form of boosting morale, as you say. What happened on Sword Beach? Were they met with very fierce opposition there or was it quite an easy stroll ashore?

Peter Caddick-Adams: The shorthand is that the worst punishment was meted out to the Americans at Omaha Beach. Therefore, the reception on the other beaches diminishes by comparison. The fascinating thing is that if you drill down and you start to talk to the veterans of each and every beach, and I've spoken to many who fought on each beach, they all actually had a very rough ride. The assault waves on any of the beaches were equally likely to be shot, sniped, killed or drowned. A huge number of people drowned before they even got to the beach because the weather was so rough. The English Channel and drowning accounted for 15% of the casualties on D-Day itself before anyone was even shot. Once you get ashore, a lot of the injuries are caused by shellfire. Sword Beach, for the assault battalions that arrive there, is in many ways just as bad as Omaha Beach. The difference is the Americans defend Omaha longer and, therefore, the casualties are higher. Whereas, the defenders at Sword Beach are overcome within the first couple of hours and that's the difference.

Peter Moore: So if we talk about 7.25, they're going ashore and by late morning, they've established a beachhead.

Peter Caddick-Adams: That's the case along the other beaches as well but because of terrain and high cliffs at Omaha, the Germans are hanging on for longer and it will probably take four or five hours for most of them to be overwhelmed and that's the essential difference. It's snipers who cause a lot of the damage. If I go back to Bill Millin, he later meets a German prisoner who said to him, 'I was a sniper and I had you in my sights,' and Millins said, 'Why didn't you shoot?' The German said, 'Because you're mad. You're mad standing in front of your men playing that instrument. Of course, I wasn't going to shoot you. It would waste a bullet. You're bonkers!' [Laughter]. It's a lovely, lovely story.

Peter Moore: It is and I certainly had no conception or hadn't thought at all about musical instruments being used on the beaches but if we loop this back around together and go back to Operation Fabius, which happened almost exactly a month before, is what happened on 6th June a consequence of that good planning?

Peter Caddick-Adams: I interviewed a platoon commander years ago about D-Day and before I even started, he said, 'Let's look at the training because the success of D-Day was down to the training and getting it right beforehand.' What makes D-Day successful is you're flung ashore, you're cold, wet and probably suffering from seasickness. The moment you're under fire, your friends are going down and you're very lonely because you're often hiding from the shells. That's where your training has to kick in and if your training hasn't been any good, you don't know what to do. Fabius confirms all this training. Some British soldiers had come back from Dunkirk and had not fought the Germans since 1940 and they had trained for D-Day for four years. That's how long the training is for some people but certainly a year for everybody. We lost more people training in the year before D-Day than we actually did with soldiers killed on D-Day itself.

Peter Moore: That's a really striking statistic, isn't it?

Peter Caddick-Adams: Getting the soldiers to France is only half the battle. Sustaining them while they're there is the other half but also, you have huge redundancy for the unexpected to happen. The rough weather causes a delay for 24 hours. We can cope with that because we've got enough extra fuel. The German Luftwaffe occasionally appear or don't appear but we've got means of dealing with that. We can stop the German reenforcements coming up because we've briefed the French Resistance about what to blow up. There's a huge array of different plans. How do you get tanks ashore through the rough surf? We create swimming tanks. What do we do about logistics if you haven't captured a port? We design our own and toe them across the Channel.

Peter Moore: The famous Mulberry harbour.

Peter Caddick-Adams: The famous Mulberry harbour. They are the tip of the iceberg because we go into all sorts of special innovations. Innovation is the key and not just training. We are so good at that in the Allied Forces and get better even during the unfolding campaign.

Peter Moore: It's an enormous story and we've only been able to scratch the surface really but what you've given us is some really strong human perspectives that go from the king making his speech at that meeting to the piper on the beach, which is an image which is actually going to linger with me, I think, quite strongly. Also, let's move out of your travels now and just talk a little bit about the book for a couple of minutes. Obviously, we've been talking about preparation and logistics here. Your book is structured...

Peter Caddick-Adams: The structure of the book is that the first half is the training and the more I wrote about the training, the more I researched it and I drew on the interviews I've done. Of course, I've been, in many ways, researching D-Day ever since I walked those beaches first in 1975. I've interviewed, over the years, over 1,000 people who were, in some ways, associated with Operation Overlord. I wanted to draw as many of those in as possible. It's all the training; it's the three million Americans in England; the love affairs they have; and the way they changed our society. They brought Spam with them. They brought nylon stockings. They brought the first freeze-dried coffee, Nescafe. It's part of our culture. They were criticised for being oversexed, overpaid and over here and they would retort that we were underfed, undersexed and under Eisenhower [laughter]. There's all of that wartime repartee but they made a huge impression. I think just at the moment when Britain was at its most austere, drab and unpleasant in the middle of wartime, the Americans arrive with colour, music, Glenn Miller and their rations and all of a sudden, they give the entire population a lift that they desperately need. They come with their own rations and nobody has seen peaches for four years and things like this. It's partly that effect and it's the beginning, of course, of the special relationship. This is why American presidents have come over for the key anniversary moments ever since.

Peter Moore: We've got one on the way very, very shortly, I believe. It's 75 years ago. How should we look back at D-Day now, do you think?

Peter Caddick-Adams: You can't get away from the fact that it's become the shorthand for the Second World War. Dunkirk, perhaps, is really important for us. I was really struck by the way the sea actually dominates our story of World War Two. For the British, it's leaving France in 1940 from Dunkirk. For the Canadians, it's coming across the Atlantic. For our survival, it's all the supplies and ships that come across and dodge U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic. For D-Day, it's mounting this great assault across the English Channel and sustaining it. It is very much a story of the waves but for us, I think if you want to encapsulate World War Two in one day, it's 6th June 1944. We look back on that as the beginning of Europe's freedom and even the Germans do. I was very struck at the time of the 50th anniversary, which is when the Germans really began to participate, that they regarded 6th June as the beginning of their freedom as well from the Third Reich. It was the beginning of the end of Nazi tyranny. It was the beginning of the liberation of the occupation of France. In many ways, it is the end for Germany and the beginning of something else for the whole of Europe in different ways.

Peter Moore: That's a wonderful way of explaining the great resonances of the story. At the end of these podcasts, I like to throw a bit of a curveball. We've been metaphorically travelling around our three scenes and I always like to ask people if you could bring one tangible object back from this time, 1944, to today and you could have anything you like, what would you like to get?

Peter Caddick-Adams: I've done my best to bring a lot of tangible objects back from various battlefields. You should see my office.

Peter Moore: You can have another one [laughter].

Peter Caddick-Adams: I can have another one. One of the American paratroopers, who was landing in the middle of the Cherbourg peninsula, gathered his men together and in the small hours, they heard a staff car rumbling towards them. They shot at the staff car, it ground to a halt, a German officer tumbled out, they shot him and his hat rolled away. One of the officers picked up the hat and inside was the word 'Falley'. That was the surname of the first German divisional commander, a general, to be killed in Normandy. Because he's killed, the Germans don't know how to react in that part of Normandy. If someone were to magically bring me his hat...

Peter Moore: That's what I'm proposing. I have it, metaphorically, here. I'll pass it to you [laughter].

Peter Caddick-Adams: It's a metaphor for why we do so well because D-Day comes as a surprise to the Germans and at the end of the day, they don't know how to react. They are surprised and it's the loss of so many of their senior commanders in the first few days that means the lower echelons are running around like headless chickens. The killing of General Falley in the very first hours of D-Day underlines the fact that we wrongfoot the Germans. We cut off the head and the rest don't know what to do.

Peter Moore: Well, we have his hat. We have a wonderful conversation. Thank you very, very much today, Peter Caddick-Adams, and all the very best with your book.

Peter Caddick-Adams: Thank you very much indeed. It's been a huge pleasure and a real privilege to commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day.

Peter Moore: That was me, Peter Moore, travelling back to the events of 1944 with Dr Peter Caddick-Adams and talking about his book, Sand and Steel just the other day. The book is out now. What really is going to remain with me, I think, after our conversation is that picture of the piper on Sword Beach, walking up and down in the early morning light and playing his bagpipes. It seemed to me a strangely humane and powerful image. Many thanks to Ryan Bernsten for giving us a little blast of Dwight Eisenhower right at the start of this episode. He's got his own podcast called Fifty States of Mind which is all about modern US politics. You should go and check that one out. I hope you enjoyed this episode of Travels Through Time. Please leave a comment or subscribe to our feed to get the first news of new episodes. The next one will be out in a fortnight's time but from me and for now, that's it. Thank you very much for listening.

[Sound of ticking clock]

Transcribed by: Podtranscribe